The foundations of FastHTML

ASGI

FastHTML brings together and builds on top of two well-established, astonishingly flexible, performant technology frameworks: ASGI (implemented in Uvicorn and Starlette), and HTMX.

ASGI is a small but incredibly clever approach to simplifying how HTTP, the foundation of web communication, works. It converts all the different parts of an HTTP transaction into a basic, well-defined Python API: a single function, which takes three parameters, which provides access to the full HTTP specification.

Uvicorn is the ASGI server used by FastHTML—that is, it is responsible for listening for HTTP messages, and converting them into the Python ASGI API. Then Starlette is responsible for taking this powerful single-function ASGI foundation and making it more convenient for programmers, by adding a small number of functions and classes that remove the boilerplate you would otherwise need to support ASGI. As a FastHTML user you very rarely need to know anything about the ASGI/Uvicorn/Starlette trio, other than that it is there in the background doing a lot of work for you!

To learn more about how Uvicorn and Starlette work in FastHTML, see the relevant technology section.

HTMX

HTML on its own provides only the most basic interaction mechanisms: you can click on a link to “get” an HTML page, or you can click a button on a form to “post” form data. In either case, the HTML result from the server replaces the current page (known as a “full page refresh”). These limitations have been there since the earlier days of the web. HTMX is a library that removes them, by removing four key constraints:

- Any element on a page can call the server, not only links and forms

- Any event can call the server (e.g. mouseover, key-down, or scroll), not only clicks

- Any HTTP method can be used to call the server, not only “get” and “post” methods

- The server response can be used to modify the existing page in any way, deleting elements, adding elements, or changing elements, instead of only replacing the whole page.

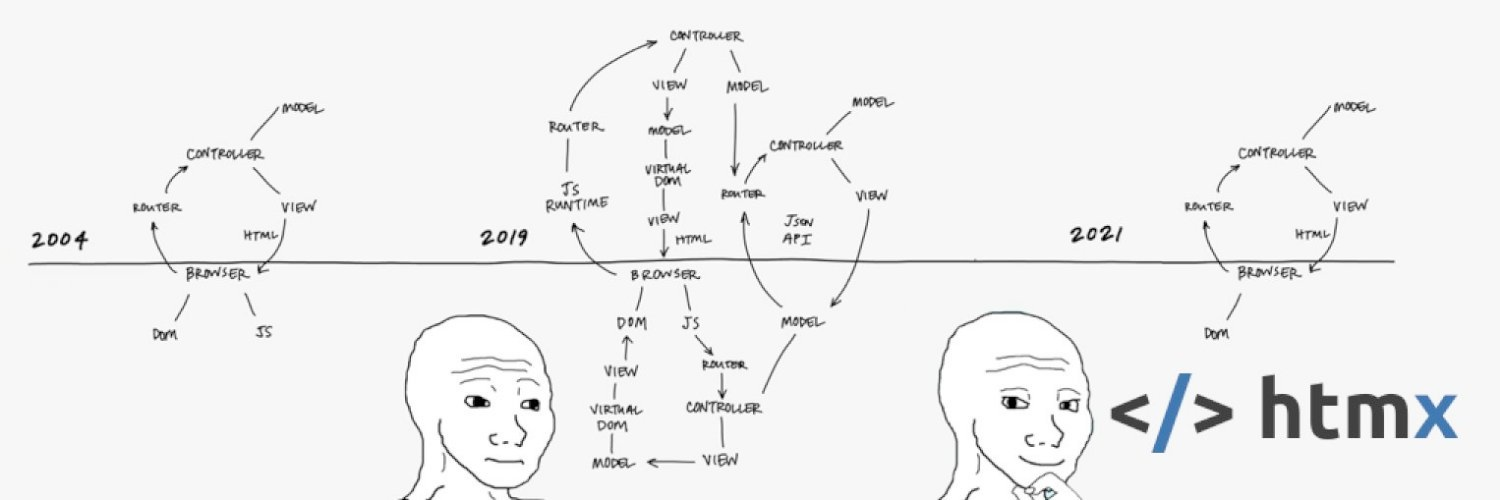

HTMX was previously known as Intercooler. It is now over 10 years old—so it’s a mature technology. HTMX/Intercooler is responsible for the idea that we can build on top of the fundamentals of the web, without sacrificing the ability to create modern, interactive web applications. Without it, FastHTML would not exist. HTMX is famous for its memes, including the image above, which highlights how HTMX’s approach returns us to the simplicity of the early days of the web (although perhaps now we should update that meme to FastHTML 2024, where we would have just 3 parts: browser, DOM, and a python file!)

To learn more about how HTMX works and how to use it, see the HTMX technology section. To understand the benefits of using HTMX in practice, watch this talk, which goes through a real case study of using HTMX to replace React in a complex large application. It shows how HTMX allowed the amount of code to be drastically reduced, the speed of the site got faster, and they were able to simplify their team structure by removing the need for frontend specialists.

HTTP

All web page requests are made by your browser, and returned by the web server, using HTTP. Many web programming systems attempt to hide this from the developer, but FastHTML (and the underlying technologies Uvicorn, Starlette, and HTMX) does not. By surfacing this, it means you are working directly with the foundations of the web, not through frequently-changing leaky abstractions. HTTP is, at its heart, a simple text protocol that underlies all web communication. It starts with a request, e.g:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.example.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0

Accept-Language: en-GB,en;q=0.5

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, br

Connection: keep-alive

The first line shows it is a GET request for the root URL (/). The next lines are headers, which provide additional information about the request.

The server then responds with a status code (here 200, which represents success), headers, and the content, e.g:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Wed, 08 Jan 2024 23:1:05 GMT

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

Content-Length: 5

Server: Apache/2.4.51 (Unix)

Connection: close

hello

When you understand that all web applications communicate like this, and your programming framework lets you easily interact with this, you will have no limitations on what you can build. Having said that, working directly with HTTP’s text protocol is not easy, which is why the higher-level ASGI protocol exists. It makes all of HTTP available to the Python programmer in a simpler form. In addition, HTMX allows the browser to more fully utilise HTTP.

HTML/CSS/JS

In the previous section, the server responded with the body “hello”. But in practice, web server responses today generally are either HTML or JSON. With FastHTML (as we’ll see in the HTMX technology section), our responses are nearly always HTML. Here’s an example of a basic HTML page with a header and a body containing a paragraph (<p> tag).

<html>

<head><title>Example</title></head>

<body><p>Hello World!</p></body>

</html>

HTML creates structure, and the browser converts the HTML internally into a Document Object Model (DOM) element tree. To add styling to the browser’s representation of a document, we add styles using CSS. One approach is to manually define styles in a CSS file—for instance here’s the stylesheet we’re using for the site you’re reading now, with the CSS rule which gives the above HTML block a light grey border and background.

Most styles in most FastHTML applications won’t be manually defined, but instead will come from a CSS framework like Bootstrap, DaisyUI, or Shoelace. FastHTML makes these easily available as FT components.

Although most of the logic of your application will generally be written in Python and made available over HTTP using FastHTML, you might well want some self-contained UI updates to happen directly in the browser. For this, you can write JavaScript and add it to the web page using FastHTML. This is not often strictly required, but can make some parts of your app faster, more concise, or add some convenient functionality from the browser’s DOM API. For instance, we often add a “Copy” button with sample code in our apps, which requires using the DOM API, and therefore requires adding a little JavaScript. JavaScript was originally designed for this purpose, so it’s a particularly good fit for adding client-side behaviours to applications.

To learn how to add JS libraries to FastHTML, it can help to look at examples. FastHTML includes modules for a number of popular JS libraries, such as Marked.js. To see how this is implemented, have a look at the seven lines of source code for MarkdownJS in Python.